This is the second essay as part of my MA study in 2004. Like the last post this one was written when the social climate was demonstrably different from the one we find ourselves in today. It has been added here as an early indication as to my thinking when I first thinking about portraits and the role they play in our society.

Portraits in Contemporary Society

This essay is an exploration of what portraits are and how they are read in today’s world. Through understanding the role and function of portraits in general, and how that function has changed with our shifting notions of what constitutes our modern identities. I hope to begin to formulate a framework for the idea of a modern portrait as an image that fulfils the basic requisite as a function of “likeness”, which simultaneously places it firmly in the present with our understanding of our place in the world. This includes current ideas about social/political thinking about community, identity and subjectivity and how wide ranging social and political events such as the Brexit referendum has had a direct and profound influence upon how we, not only see ourselves, but how we act, move and exist in this world.

Identity is at the core of every social movement and it informs who we are and how we are. It shapes and forms our understanding of our place in the world and defines the laws we create for ourselves and by which we live. The notion of subjectivity, and its manifestation within the visual arts is a complicated and vexed one. Its role and authenticity in contemporary life and the way in which various strategies and agendas are employed to find a satisfactory expression; points to a specific and highly mediated understanding of what this can be. In the light of the recent decision to leave the EU this has become an almost impossible issue to resolve. Clarity is hard to reach and satisfaction impossible to sustain. Richard V. Reeves wrote that Brexit crated identity politics defined not by who we are but what we are against. That being “British” is defined by not being European. The referendum took away our ability to know who we are and replaced it with the notion of identity of subtraction (we know who we are by knowing what we are not). Focus on this issue appears to be is coming from the radical fringes at the edge of these arguments, where polarised versions of self (radicalised, racist and fascist) are now becoming the accepted norm. The Brexit referendum was a referendum about the identity of the UK and its inhabitants and as Scot Nakagawa states “Facts lose their power when Identity is in play”. How is he portrait going to react to these issues? And what will a visual representation of identity look like in the light of the confusion brought forward as a result of the collapsing social/political framework on which it is hung? The traditional portrait is a highly political image, and in this age of political flux, not to mention gender fluidity, sexual experimentation and the ability to create new virtual representations of the self, can the need for a “likeness” be reconciled with the inability to find a satisfactory visual lexicon with which to do so.

What is a portrait?

Portraits are about the inherent need to express identity. To give shape and form to the understanding of how individuals see themselves in the world at large. The fundamental desire to know who we are, where we are, and how we fit into the world around us, are also dealt within the portrait image. The portrait is an expression of both the subjects desire to know, and the artists’ ability to reveal. No other genre of painting deals with these issues in such a direct and confrontational manner. It engages directly through the form and structure of its language those elements that other forms of visual art can only approach obliquely.

A portrait must contain within its own existence some form of recognition of its subject. This has been traditionally a physical one. The image must, in some way bare some resemblance to the subject of the portrait. This relies on the viewer having some knowledge of who the subject is. This can obviously vary from one person to the next and also vie from intimate knowledge of the subject to none at all. What we do not know about the subject we have to make up. In this case, we have to make assumptions about the person depicted from the clues given to us by the artist. The nature of these clues is reliant on our understanding of the symbolism used, the artist’s ability to link these clues to the subject and the ability to place these clues into the context in which we can, as the viewer, understand. In the current social/political climate artists (as individuals as well as creative practitioners) have an increasing duty to reflect the way in which notions of identity have been usurped by “Political” agendas. These agenda utilise the need for understanding to put forward their own entrenched, radical agendas. Identity (and by association the portrait) has become the means by which to dismantle the traditional frameworks and narratives used by communities and individuals to form the required networks of subjectivity; and to confuse, control and exploit society through a continue onslaught on its validity, authenticity and value.

With regard to the drawn or painted portrait the intensions of the artist have to be considered. The traditional and most prevalent approach that an artist takes in making a portrait is rooted in the commissioned portrait. An individual or an organisation approaches an artist to create an image within their parameters of what they consider a portrait to be. By this I mean a representation that conforms to the clients understanding of a portrait image. This is one of the methods used to control our notions of community/identity/ subjectivity (we have moved on from this with Brexit and post truth Trump. To be covered later). A traditional contract that creates a strict hierarchy of who is “worthy” of identity (the subject) and how that is going to be expressed (the commissioned portrait process) and to what end (if any) this will be presented to the outside world

The portrait, more than any other genre depends on a tacit understanding between the viewer, the image and the artist. The nature of that understanding is flexible, but no other form of image making relies on such a contribution from external sources as the portrait process. The advent of modernism and the technical development of processes such as photography, digital and virtual imagery have led to the portrait becoming a viable means of understanding not only how world looks but also how it feels. After all our psychological and technical evolution is the symbolic reflection of our need to understand. This flexibility is its greatest asset, but also makes it susceptible to abuse and exploitation. Especially without due diligence on the part of those who would be abused and exploited. Identity has become a sop, something to keep the masses happy as they slowly strip us off the means, knowledge and experience of self. The term “portrait” has to become a POLITICAL one.

Using the same layout from Portrait Detectives: Lesson 1 Identifying and Understanding Portraits[3] we can begin to formulate our own notions of what exactly constitutes a portrait image. On that satisfies both the traditional and accepted idea of what a portrait is whilst articulates a new understanding and experience of community/identity/subjectivity in the light of current thinking and events.

What is a portrait?

- A portrait is an image of an individual which expresses its primary aim to create a recognisable likeness of the subject.

- Traditionally the portrait is a political act of constraint and subjugation, by which I mean it is a deliberate act of creating and sustaining social, political hierarchies that reflect the Empire state and enforce a power elite and class structure and other frameworks.

- The term ‘portrait’, one that reflects a new understanding and experience of community/identity/subjectivity has to become a POLITICAL one.

- It will ensure that is shifts from a passive position to an active one.

- Portraits will need to free themselves of the patronage of the commission contract. This is because it constrains and constricts the expression of identity within the tired, failed power structures of the Empire state.

- Social change will ensure that this process can take place.

Why do artists paint portraits?

- Artist who paint portraits usually do as part of a commissioned contract. In this case they paint portraits to maintain an acceptable standard of living.

- Artist paint portraits because they subscribe to the Empire state which grants them this standard of living.

- As such they become willing participants in the dismantling of the frameworks required to create sustainable narratives on which to build new experiences of community/identity/subjectivity.

- Artists who paint traditional portraits are passive in their expression of notions of identity.

What questions can I answer? These questions may include

Subject

- Who is the person in the portrait?

- Is the person famous/powerful? Is the identity of the subject reliant upon the viewer recognising them, i.e. are they famous, a celebrity?

- If so does the person in the portrait express their identity through the accepted portrait conventions?

- Can the identity of the subject be expressed through the rejection of these portrait conventions (this will mean that a POLITICAL expression of identity will need to be expressed?

- The subject of the portrait has to change from a passive one to a POLITICAL one.

- The subject of the portrait has to come to terms with the fact that whatever their expression of their identity is it has to be seen as a willing participant within a political agenda.

- If the subject of the portrait is not famous/powerful (they will not be the subject of portraits under conventional means) how can their identity be expressed through the rejection of the accepted?

- Besides the person, himself/herself, are there any other objects in the portrait that give the viewer any clues? (objects that the person is holding, objects that are in the background, props such as chairs, tables, etc.)

- Collaging different elements from alternative sources that challenge the traditional notions of portraiture.

- Collage brings together the POLITICAL expression of community/identity/subjectivity.

- Collage has the ability to bring together different elements to create new meanings. This can be utilised to redefine our expectations of community/identity/subjectivity.

- Does the way the person is standing or sitting tell you anything about them

- The source images can be from found sources such as publicity photos and other external sources.

Set Up

- How has the artist arranged the portrait?

- Do you think the person posed for this portrait?

- Posed portraits are a lie. No one exists in such a manner as the posed portrait. We breath, blink, smile and move all the time.

- Posed portraits are designed to be documents of control, oppression and exploitation.

- The posed portrait can be reassigned to serve an alternative expression of identity.

- A more focussed and accurate portrait can be achieved through creating informal source images through ‘snapshots’ taken during informal conversations.

- Where is the person looking (at the viewer, away, at something else)?

- Is the portrait realistic (looks absolutely real) or is it abstract (the artist was thinking about something real, but altered the visual reality of the subject in some way).

- The portrait relies upon being a realistic image.

- Realism is not fixed and is in a constant state of flux.

- The artist has to decide where realism lies and what it is.

By applying these sets of questions, we can develop a set of criteria that will form an analytical sense of what constitutes a portrait image. These do not take into account the viewers own personal aesthetic sensibilities and tastes but they are the means by which we can apply our individual senses onto the image. We need to know what we are looking at before we know how we feel about it.

Using the headings suggested on the previous pages I will attempt to define a number of images that I consider to be portraits. These images are not necessarily traditional portraits but images that I feel I am drawn to in some way that incorporate much of what I consider a contemporary portrait to be.

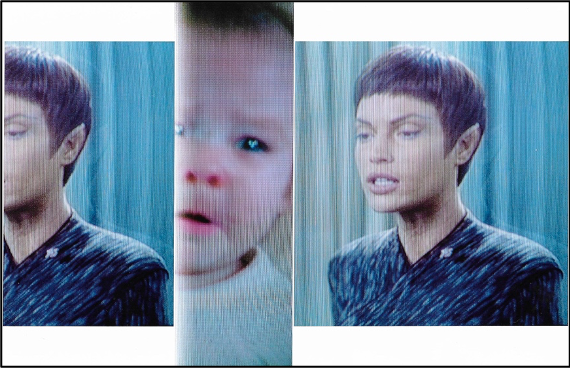

Firstly, the idea that a portrait is an impassive image is unsatisfactory. The static image of an individual, looking blankly at the artist/viewer or gazing into some imaginary pace is inappropriate. The human face has more moving parts in it than any other part of the body. To accept an image of it in a passive unmoving manner seems absurd to say the least. Faces move, mouths talk, eyes blink, noses twitch, lips smile, a portrait which depicts, or in some way acknowledges this reality is surely going to contain a greater sense of truth that one that does not. I have taken a number of images directly from moving images found on television. This was done to capture the face in its natural element, moving in the course of communicating. These images show a deeper/different understanding of the human condition as they reveal a level of reality that we take for granted in our everyday lives and is by and large ignored in portrait painting. The faces depicted here are in the actual process of existing (Fig 2). This relates more directly to the moment that these images were captured than some deeper understanding of the subjects. In turn this will detract the viewer’s ability to understand the subject, because they are not directly relating to the him or her, but as a result it is a more truthful image because in reality the subjects of these images would in all probability have no contact or reason to contact the viewer. It is only the portrait genre that the viewer has such expectation and power within the trinity of the elements that form the relationships involved in a portraits existence

This leads to issues regarding understanding and expectations, not only towards the image itself but also our understanding of the subject. Pietro Annigoni’s portrait of the Queen (Fig 3) is a good example. My reading of it is that it says nothing about the queen as a person but remains eloquently detailed in its understanding of what it is to be queen and the fact that it is in this role that not only do we understand and identify her but also how she sees herself. Her identity is as a monarch not as wife, mother or even a woman.

The reason I believe this to be a successful portrait is because I have no other terms of reference for the subject other than the one depicted. I have no understanding, or wish for understanding in any other context other than as Lizabeth as queen of Great Britain. For me she is not a person but an institution, a tradition that goes back centuries, and the portrait of her eloquently depicts her in this context. So, what does this man for the portrait painter? Should he/she try to go beyond the surface of the subject, to reveal a greater understanding of the personality of the subject, an inner truth, or should they just deal with the surface perceptions presented to the public by the subject. Which approach is the more realistic and conveyor of a greater sense of understanding?

The answer to this question can only be found when the artist starts the specific painting. He/she must understand what exactly is the context for the image, who is it form, and how does the subject understand themselves to be within the context of the image.

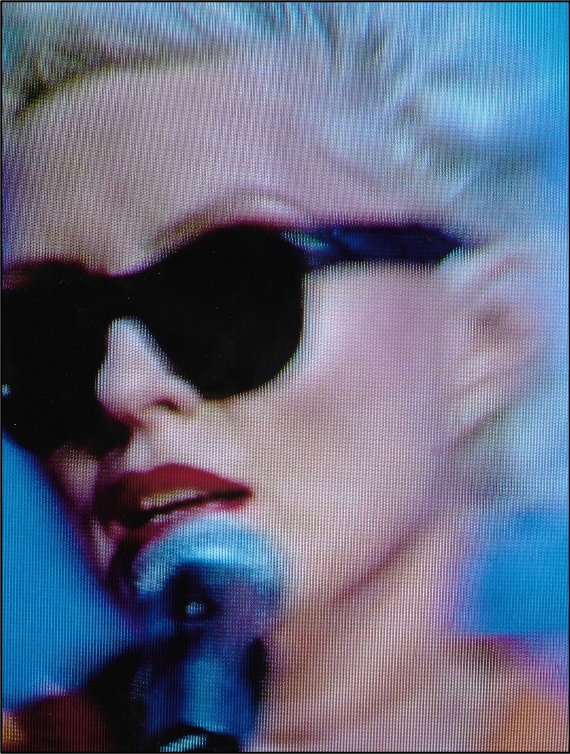

In the image of Debbie Harry of Blondie (Fig 4) I wanted to show that my perception of her was solely as a singer in a rock band. I wanted to show my understanding of what my experience of her truly is. I have never met her, or am I likely to. My one abiding memory of her was on Top of The Pops singing Denis Denis wearing a long red shirt and thigh length boots. My experience of her identity has been forever rooted in that image and her subsequent career as a singer. So, to depict her doing what she does best, in the context that she has always presented to me, on television performing, seems to me to be a much more real assessment of her identity, as I understand it, then if I was to get beneath the surface identity and reveal something of her true character. This does beg the question that this image I have produced is her true character. In this age of our ferocious desire for celebrity and fame, identities are becoming shallower and shallower until what we see is literally what we get. We have people who solely exist as their manufactured selves. They exist exclusively on the edges of our understanding with their hyper identities that cannot exist beyond the boundaries of the gossip pages and the TV screen.

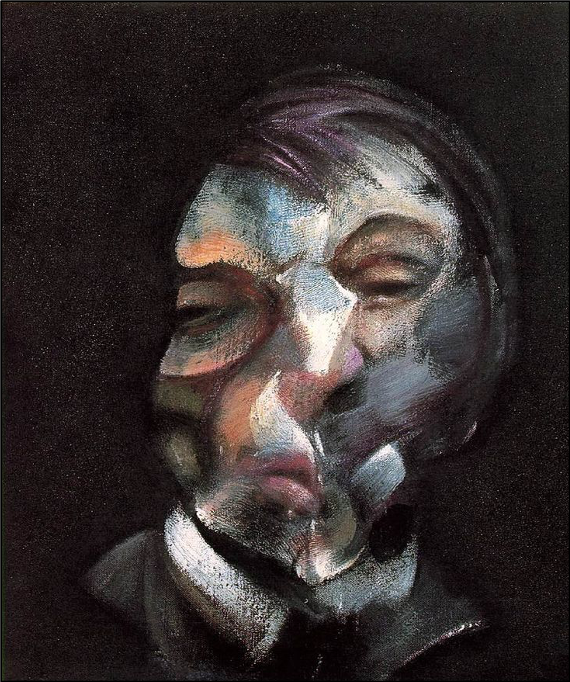

But what of the artist? The role that he/she plays within the portrait process is largely secondary to the image and the subject’s desires. Thy act as facilitators to the conclusion that it is the finished image. Their role is negated and they are no more that artisans with little or no input into the reading of the final image. It is true that they can contribute something to the understanding of the subject depicted but this is manufactured through their style and technical understanding of the media used rather than the premeditated or conceptual contribution to the reading of the image, this is because the role of the artist in the portrait process is little more than that of an employee doing a job of work. They have to create an image that conforms to the understanding of the sitter’s view of their own identity, the person or organisation that have commissioned the portrait, and the notion that a likeness of a person is reliant upon a narrow set of rules which cannot be broken. The problem is that to make an image the artist must adopt a more egalitarian stance, with his or her own desires and need for self-expression being put on the back burner. However, this only applies as long as the artist continues to conform to the accepted and traditional function of portraits and portraiture. But to break this tradition the artist has to acknowledge a new understanding of the role of the portrait and how that role is to be expressed. We can see this in the work of Francis Bacon (fig 5) how the result of a conscious effort on the part of the artist to inform the portrait with his own sense of self can affect the final image.

The result is that the work although obviously, a portrait in the traditional sense is distorted by Bacons assertions onto the image itself. These influences are rooted in Modernism and particularly the advent of photography as a mass producer of the portrait image. Bacon understood that the photograph would simultaneously undermine the power of the painted portrait whilst opening it up to a radical revaluation. He was able to use both the photographic image of his subject, as well as his knowledge of the subject, they were images of his friends, to reveal a greater understanding of not only the reality of the sitter but the relationship between the sitter and the artist. Bacon openly stated that he could only do what he did to his sitter’s portraits because he had formed a close understanding between him and them. The power of these images lies in this relationship.

From this we can deduce that the existence of some form of relationship between sitter and artist can radically affect the nature of the final portrait. As the viewer, we have to approach any portrait made in this way with a tacit understanding of the role of this relationship. When we do this the image is both eloquently powerful to the notion of the image, its role and context, as well as an intimate portrait that explores and expresses a sense of knowing and intimacy.

Very rarely are portraits painted for any other reason than just for the sake of it (Francis Bacon being the most obvious example). Thy are usually produced for reasons beyond their own existence; it is not art for arts’ sake. They are usually produced at the behest of a third party (the commissioner) or patronage of a wealthy client. This intrinsically affects the way we approach the image, as well the way the artist creates the portrait. As stated above I believe that an intimate knowledge of the subject to be portrayed leads to a very different portrait than an image of someone unknown to the artist, yet this relationship between the unknown sitter and the artist with its reliance upon formal social hierarchies and in Britain usually the class structure is the norm. If we compare a self-portrait of Rembrandt with the court paintings of Sir Peter Lely (fig 6) we can observe this difference.

Our approaches to both images differ greatly because of the context of each portrait. The Lely portrait (one of the Windsor Beauties) was part of a series of paintings commissioned by the Duke and Duchess of York and is at first glance a form court painting of one of the leading figures in Charles II’s retinue. The Rembrandt is an intimate study of the artist, with no reason to exist other than as a whim on the part of the artist himself. We see in this image an openness that is both inviting and receptive. The Lely court painting, on the other hand, shows what was considered one of the great beauties of the time, a woman in a formal pose and a reflection of both social and artistic convention. This image is confined by the mores and values of the expectations of a court portrait as well as the artistic values of the time. The Rembrandt on the other hand, although working within the contemporary aesthetic is free and the expectations of society. This has a profound and lasting effect not only on the way we read these images but also the way the relevant artists approached them.

How does the medium used by the artist effect our understanding of a portrait?

With the advent of modernism and the development of new visual technologies such as photography and digital imagery, our understanding of how to read a portrait image has been fundamentally changed. A contemporary portrait has to be in some way acknowledges, if not embark, the nature of these changes. The artist has to employ the appropriate media for his/hr portrait in the full knowledge of how the use of the media is likely to interpreted. Oil painting and other traditional mediums bring with them the weight of art history and all that it implies. New mediums take advantage of developments in new technologies reflect a more contemporary understanding of context of the image, but suffer from the lack of weight that a fuller, more established language can bring. Somehow the portrait must incorporate the best of both worlds. The image should articulate a contemporary context whilst expressing itself in the most eloquent manner, which usually means a more traditional medium with its long established record of articulation and flexibility. The level of consensus between these two elements is solely down to the individual artist. The most important thing I that he/she must acknowledge that this compromise is essential in the production of the modern portrait image. This can be done in many different ways and combinations. In the images below I have used a centuries old medium (egg tempera) to produce these images. This medium gave exactly the kind of finish I wanted for these particular images and its qualities were ideally suited for these means, yet the source images are firmly rooted in the 20th century. I used photographic images and expressive use of colour not only because they suited my particular interest but because they formally placed these images into a modern context and therefore would have to be considered as such.

So, what does an image need to have in place before it can be called a portrait? I have tried to give an objective and unbiased summery of what I consider a portrait to be. The elements that need to be in place and the context in which the image is produced and to be understood before an image can be said to be someone rather than just a general image that in some way incorporates the human form. A portrait should contain the following:

- A recognizable likeness. The nature of that likeness need not necessarily be a physical one.

- An understanding, on the part of the artist, of the process that he/he is engaged in.

- A desire to both articulate an understanding of notions of contemporary identity and more traditional notions of individuality

- A portrait image should be involved in ‘doing something’ and should not be impasiv and still, which is totally unrealistic.

- A portrait should use any means necessary to reflect the engagement of the human form in action.

- A more realistic portrait is achieved if the artist and the subject have some form of relationship. If not, this is fine but the artist has to articulate this fact and not try to impress the idea of a relationship exiting where none is there. A portrait can be as much about the absence of a relationship as about the actuality of one. Whatever the nature of the relationship between the artist and the subject it is that which should be articulated within the subject of the image.

- The artist must understand and acknowledge within the image, that a portrait consists of three elements if it is to be successful. The subject, the artist and the viewer. Each element has to be addressed and allocated an equal share within this cartel